The 2001 in Film Project + #1: Antitrust

An introduction to an exploration of 2001 in film, plus the first movie getting the treatment...

During the pandemic in 2020, I undertook a Film in 2000 project, looking back 20 years to the cinema of the first year of the millennium. Paul Schrader once suggested that a couple of decades should pass before any film can be properly judged outside of the context and emotion of its time, and who I am to disagree? It was very enlightening looking back to a very different period of movie making.

It was always a project I wanted to continue year on year but events, dear boy, events put paid to that. Last year, as the milestone of 2000 struck a quarter of a century, I re-purposed many of those original pieces for the earlier incarnation of this blog on Film Stories, an endeavour so enjoyable it made me want to continue. To throw back 25 years to 2001 and examine around a number of films from that year to give a broad level of context over what we were watching, why we were watching them, and whether or not they were successful.

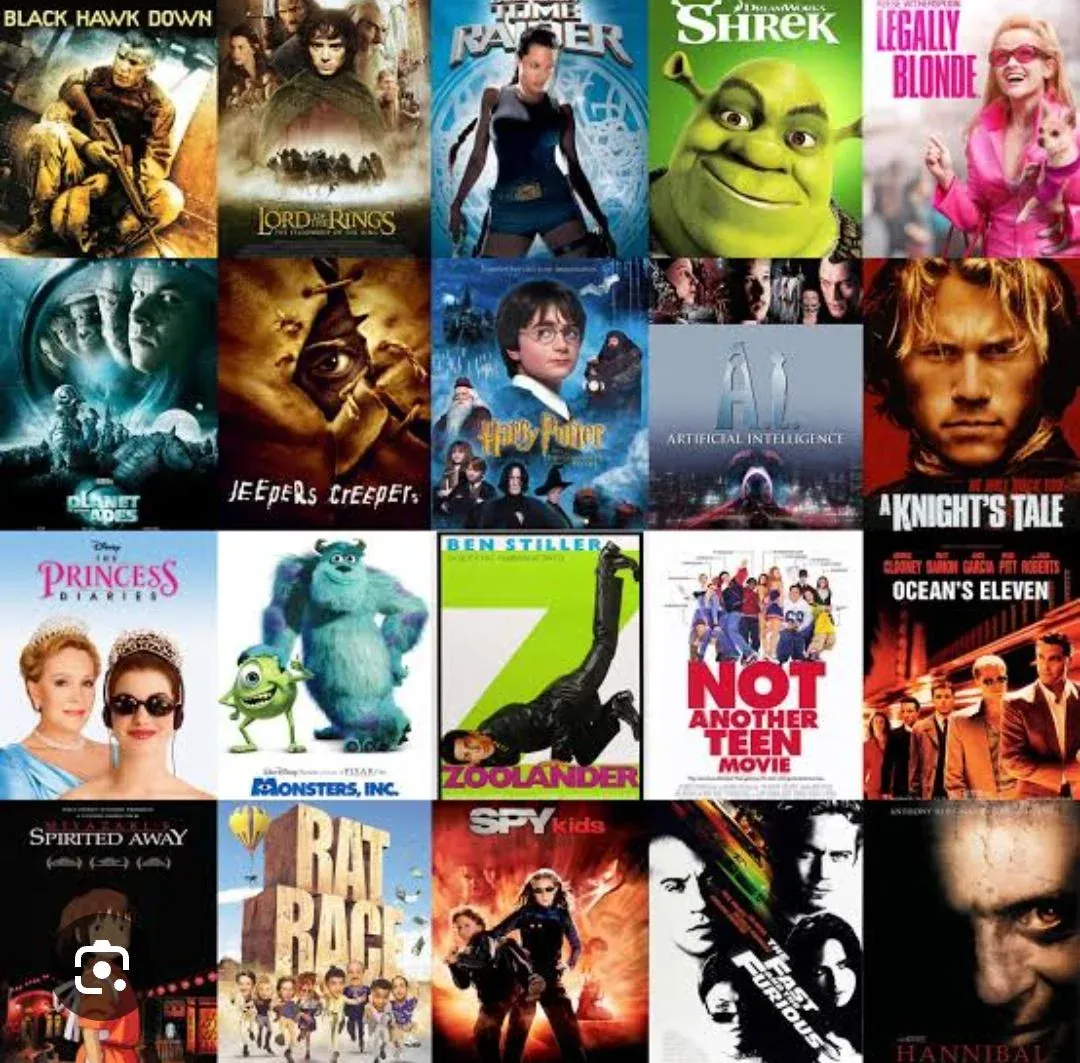

Aside from the obvious clouding factor of 9/11 over that year, and how that changed Western civilisation let alone filmmaking, one assumption I'm wondering might be disabused is my long-held belief that popular cinema of the early 2000s was largely poor in quality. 2000 certainly had its successes amidst the failures and 2001 might have Freddy Got Fingered and Pearl Harbor, but equally there is The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring and Donnie Darko. Seeing how this balance plays out will be an adventure and experience.

As a complement to this regular series, please do go and listen to At the Movies in the Noughties, developed by podcasting friend Dev Elson as a spin-off from my At the Movies in the 90s podcast, where he looks at all kinds of films from this decade. There will undoubtedly be overlap with this blog at certain points.

We start, then, with one of the first releases in January, a tech-thriller called Antitrust directed by Peter Howitt. You might not remember it...

-

Considering where we are with so-called ‘big tech’ a quarter of a century on, Antitrust looks positively quaint now. As is the case with many a picture about technology in the early days of the Internet, it is a film positively rooted in the year of its creation.

2001 began in cinematic terms with two pieces of American cinema dominant in box office terms. Cast Away from Robert Zemeckis, where Tom Hanks survived desert island purgatory by making friends with a ball, and Steven Soderbergh’s hard-hitting drugs epic Traffic, the last release of note in the year 2000. Both enormously different films. Both helmed by veterans and fronted by sizeable movie stars.

The long tail of those successes reached into January of a year that would be a defining one for American society, politics and their geopolitical future, beginning with films such as Antitrust which feel born of as much a 1990s sensibility as they do the early 2000s. Peter Howitt’s film sees itself as a high-concept tackling of the burgeoning Wild West of Silicon Valley, a landscape of young buck geniuses able to capture the American Dream with nothing but a laptop and some code.

A note on Howitt, who strikes me as a deeply strange choice for such an American studio picture as this. Formerly an actor who came to fame in a hugely popular 1980s British sitcom called Bread, based around a working class Liverpudlian family, he broke out into a directorial career that arguably peaked with his best known work - 1998’s Sliding Doors with Gwyneth Paltrow, certainly a defining career film for her and a conceptual idea that spawned terminology that carried into popular culture. Who hasn’t wondered about a ‘sliding doors moment’ of their own since that film came out?

You could therefore describe Howitt as ‘on the up’ in directorial terms, indeed despite Antitrust being a critical and commercial failure, he would go on to helm the first Johnny English film in 2003. Antitrust clearly on paper felt like a winning formula; take several popular young stars of the day and throw them into corporate espionage, the exciting frontier of the digital age, and suggest a victory of David over Goliath as the brilliant young idealists take down the cynical, power-grabbing tech overlord willing to murder in order to preserve his developing monopoly. It’s remarkable based on this just how dull the end result turns out to be.

Everyone performing in this film works the register from profoundly bored (Ryan Phillippe, a long way from relishing being twisted in Cruel Intentions), profoundly vacant (Rachael Leigh Cook, who looks spaced out for most of this) or profoundly hammy (Tim Robbins, who JUST GETS LOUDER every time he pops up on screen). It’s a heady blend of acting styles in a film directed with almost no panache or any sense of propulsion, with Howitt falling back on montage internal monologue shots or fast camera pulls to suggest revelation that have been the preserve of pastiche so often, you end up just laughing out loud at what should be a moment of import.

The sad part is that Antitrust contains ideas that are quite important to the nascent evolution of the online tech industry, even if it singularly fails to execute them. Phillippe’s Milo Hoffman, a coding genius tempted by Robbins’ not-at-all-meant-to-be-Bill Gates tech bro Gary Winston, to join Nurv (yes, really), his company developing Synapse, a new telecommunications app which feels like a forerunner to what Zuckerberg created with Facebook. It lacks the same awareness of what we might call ‘social media’ but the concept is present, even if Howitt’s film is shot through more with the latent Microsoft mentality than anything that might emerge from the bedrooms of future tech bros.

Hoffman is an example of the ‘garage startup’ trend of the early frontier of the internet, one quite different from Zuckerberg’s aegis, which posited ideas of decentralised, democratic online spaces which would be driven by passion over profit. “We believe human knowledge belongs to the world” he and his idealists confederates he starts ‘Skullbocks’ with says, but Antitrust suggests they have lost the fight already. Nascent digital corporations already are controlling the space, which is entirely what the film’s plot concerns. Winston will do anything—including kill—for a monopoly over the future, and Hoffman’s journey is one from being seduced by Synapse to seeing the danger of those behind it.

This being Hollywood, Antitrust is more interested in tapping into the 90s boom of hiring pretty young things (in this case Phillippe, Leigh Cook, Forlani etc…) and presents a digital fantasy behind the teen theatrics. Hoffman’s quest is one that provides a happy ending where Goliath is slain by David and the good guy gets the girl, with the sinister paymaster taken down. As history is proving with alarming regularity, men like Winston are rather reshaping the world to their own reality rather than being locked up by it, and this is where Antitrust’s simplicity looms large. Howitt’s film seems to believe powerful, lucrative code could indeed become open source. It feels supremely naive a quarter of a century on.

Because while Synapse in 2001 was the evil villain’s masterplan, in 2025 much of it is simply our lived reality.